Rust Binary Analyis 101 - Part 2

Background

Binaries written in Rust have proven notoriously difficult to analyze and in the previous post (Part 1), we created a basic Rust program to see what all the fuss is about. The program is intended to help us learn how Rust itself compiles commonly encountered malicious code patterns while having access to the source code to facilitate learning. Before diving into analysis of the program we developed, let’s look at what makes Rust analysis difficult in general.

Challenges with Rust Analysis

One of the challenges with analyzing Rust binaries is that the binary Rust produces can be very different from the code the developer initially wrote. This means a lot of the logic does not translate in ways we (and our tools) are used to. So when our tooling encounters Rust code, it can result in broken disassembly which further exacerbates the issue. There’s a lot of nuanced changes in Rust’s ABI that are useful to understand especially when it comes to fixing broken disassembly. I highlight a few points here; however, for further reading, Checkpoint research has a great writeup that dives deep into Rust’s features at the binary level: Rust Binary Analysis, Feature by Feature

Inherent Challenges

At a high level, analysis is complicated by the following inherent challenges which result from the Rust language/compiler and the current state of analysis tools.

- Contiguous strings: This was an initial issue with Rust (and Go) binaries that our tooling did not know how to handle. In my testing, this appears to have been solved in IDA 9.1.

- Aggressive optimization: At times, Rust’s aggressive optimization feels like it completely refactors the original developer’s code; other times it optimizes it away.

- Functions can access each other’s stack frames!

- Broken disassembly: which may result from the previous points discussed along with our current analysis tooling being so C-centric in their design.

Threat Actor Rust Abuse

Rust supports many different calling conventions and allows developers to specify them at the function level. Threat actors can abuse this to significantly complicate analysis by creating malware which uses mixed calling conventions.

Rust Binary Analysis (IDA 9.1 vs Ghidra 11.3)

Throughout the rest of this section we’ll analyze the program we developed in the previous post (Part 1) while comparing the output from IDA 9.1 with Ghidra 11.3. If you haven’t already, try analyzing the program yourself first as the following will provide a solution.

Finding User Code

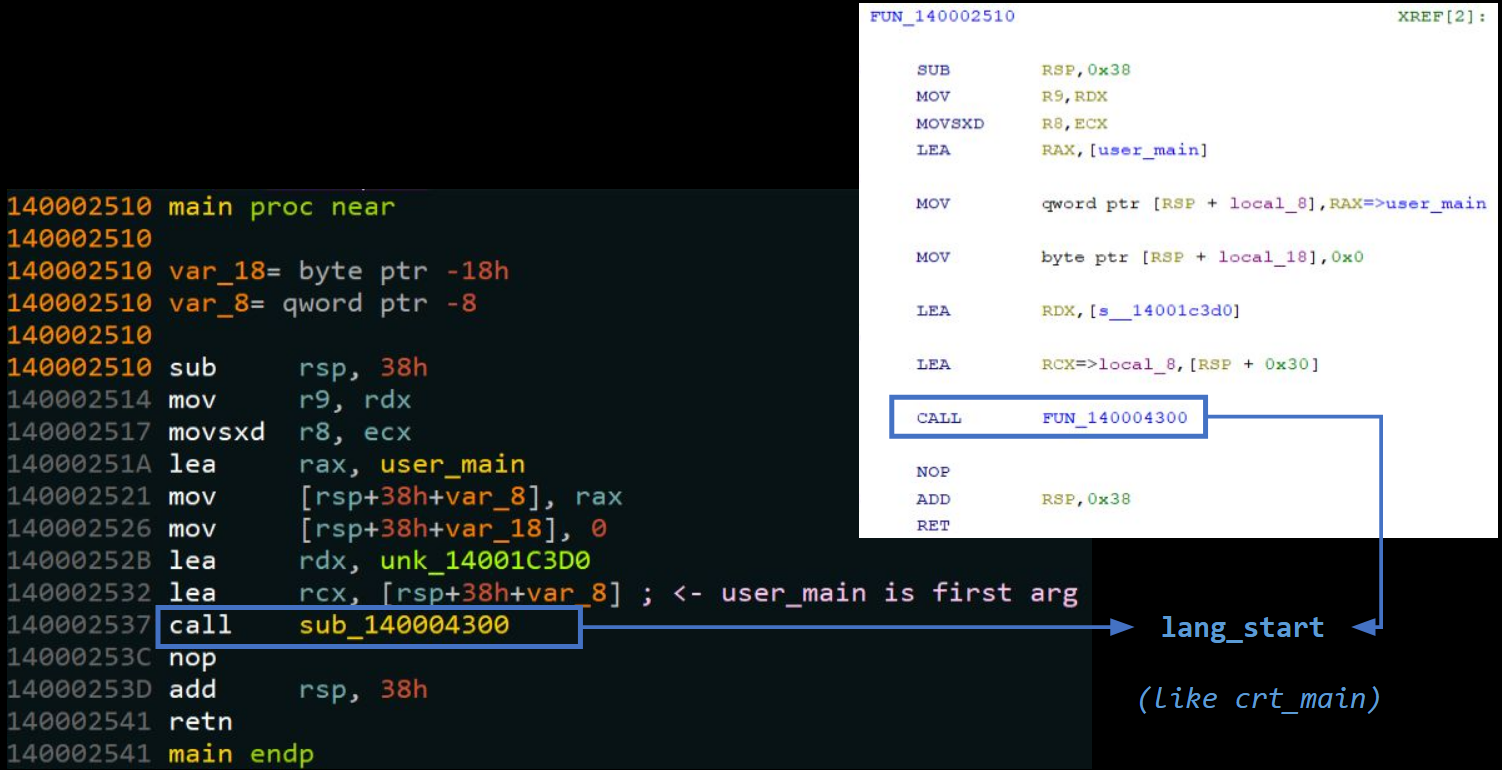

When loading up the program we wrote in IDA and Ghidra, neither has an issue disassembling the entry point; which is nothing special. The short function does not directly call the user defined main; instead, it provides it as the 1st argument to the function at 0x140004300. This function is lang_start which is responsible for setting up the Rust runtime before calling our user-defined main.

Comparing Decompilation of main

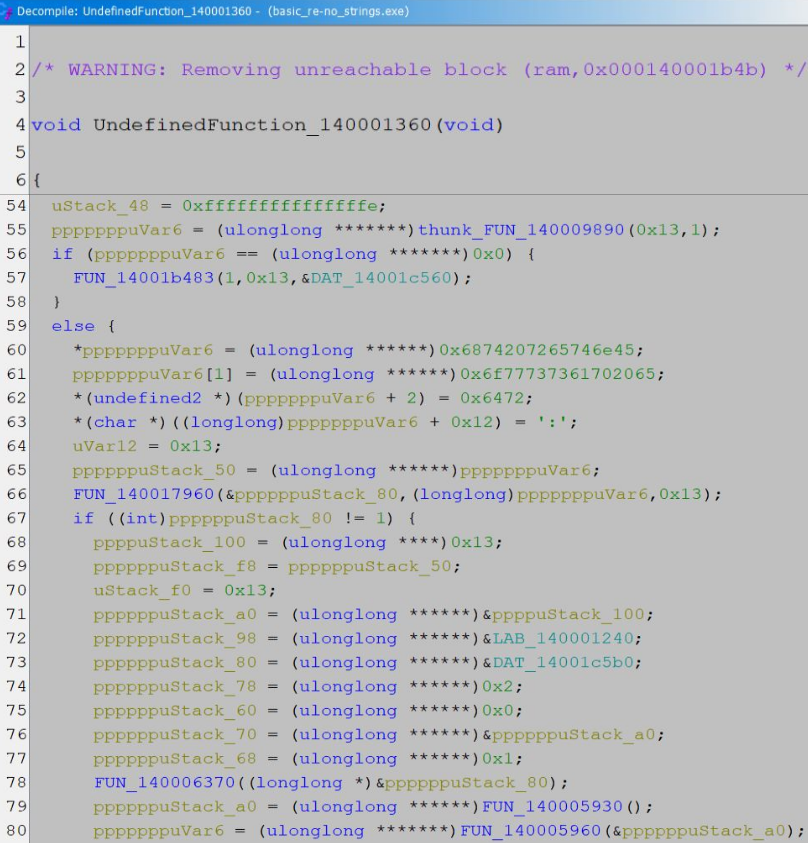

Unfortunately, as soon as we open up Ghidra’s decompilation of the user-defined main, things are no longer so simple:

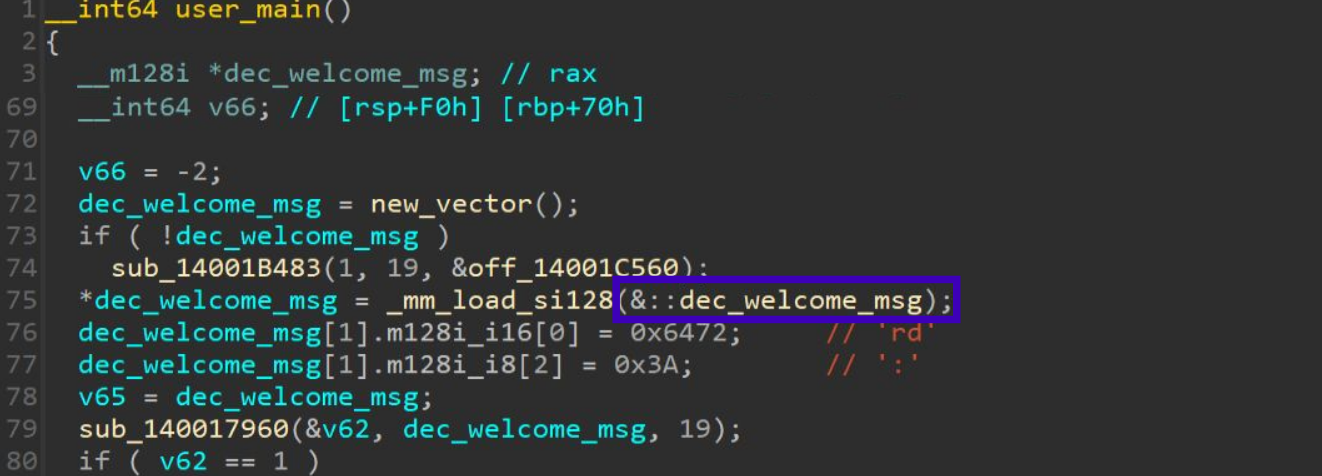

However, IDA handles this much better. Notably, IDA handles the hex arrays we added for our encrypted strings as a simple global variable in line 75:

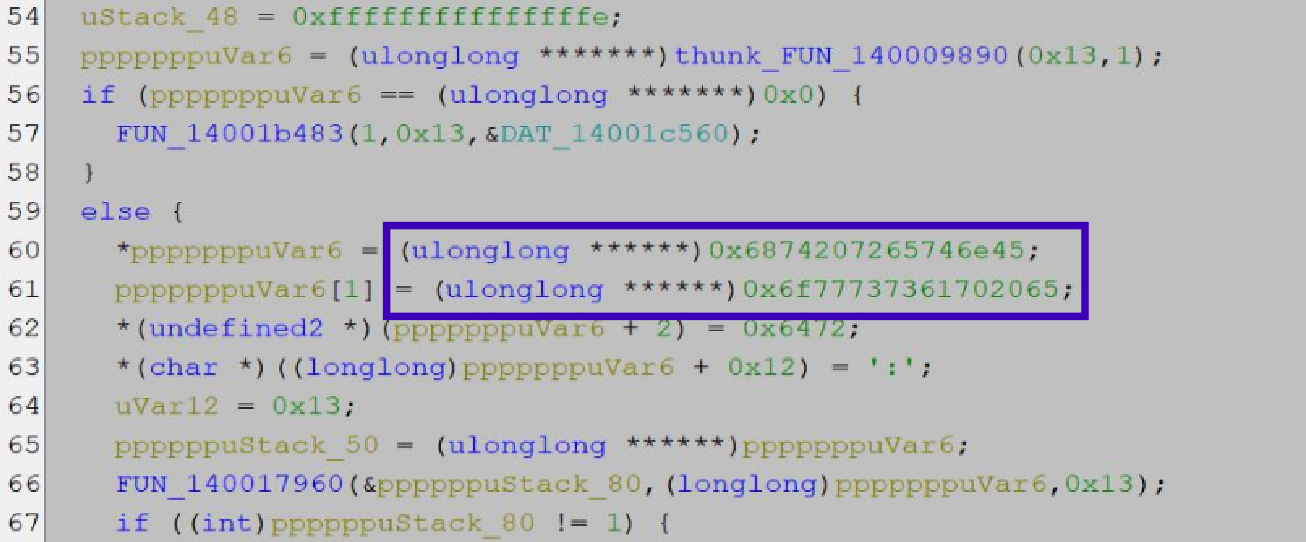

This is one of the things that makes Ghidra more difficult to understand; it includes the raw hex data in its decompilation. In this case, lines 60-61 correspond to line 75 from IDA:

As far as our analysis goes, we’ve found the start of the main portion of the user code. Let’s look at it a bit more closely, particularly the hex data from line 75 in IDA’s decompilation (60-61 in Ghidra)….

This hex data should be our encrypted welcome message, but if you’ve stared at hex values long enough… you learn that the majority of ASCII letters correspond with values around 0x60-0x79. Sooo… is this plaintext? 🤨

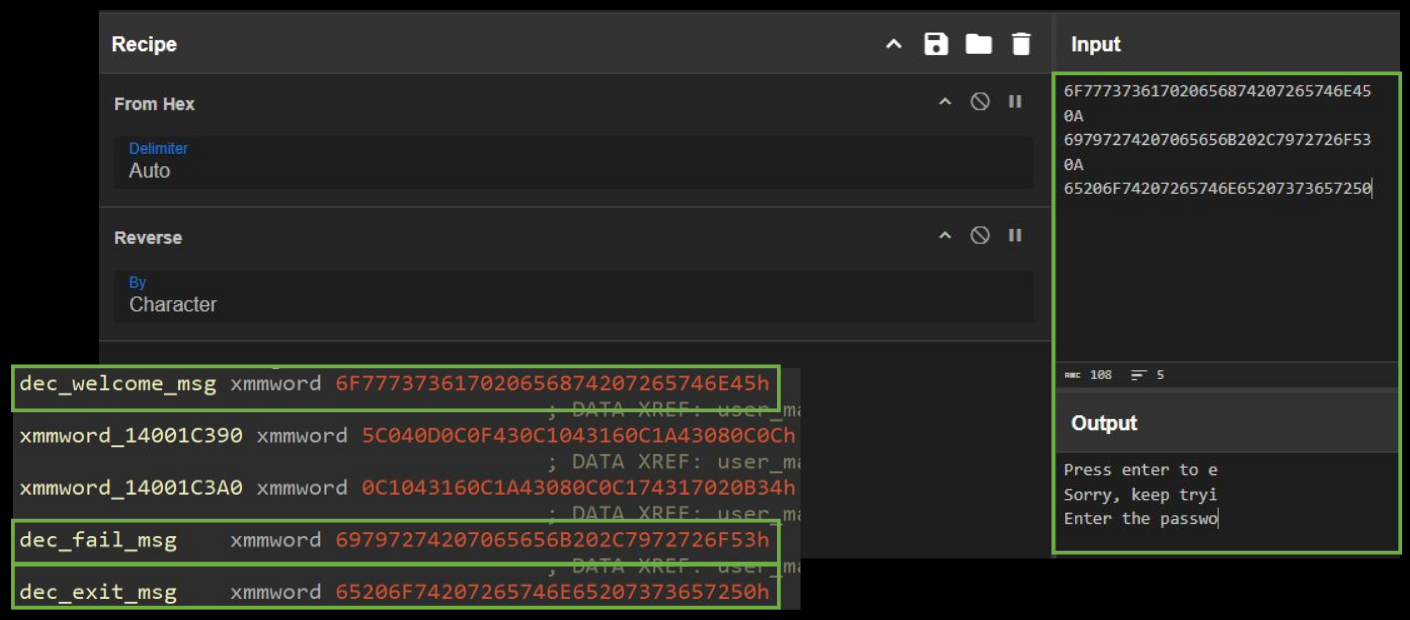

We can copy the hex value from the decompilation 6f777373617020656874207265746e45 into a tool like CyberChef and we get: owssap eht retnE. Right. Endianness. If we reverse it, we get: "Enter the passwo".

…did I compile the wrong code?

Aggressive Optimizations

I knew the Rust compiler was aggressive with optimizations, but going through this exercise, I learned that it is actually really aggressive. The Rust compiler decided to execute portions of our code, hard-code the result, and remove the original code we wrote.

Unintended Consequences

Remember when we decided to remove plaintext strings from our code to make analysis a bit more difficult? Well… it turns out, the Rust compiler saw the encrypted strings we hard-coded as byte arrays and decided to decrypt some of them so that it can hard-code the decrypted versions instead! 🫠

This is pretty surprising, that means that the compiler (by default, mind you) not only identified the hard-coded byte arrays, but also found the corresponding xor_crypt() call and executed it. I’ve seen similar behavior other compilers like gcc, BUT I had to optionally increase the aggressiveness of its optimizations.

Rust Knows Better

Another reason your code may look unrecognizable in a disassembler, is that Rust does not preserve the control-flow structure for the programs we write. Remember that helpful xor_crypt() function we wrote? Well, Rust’s compiler decided to do away with it in our program. Partially because it decrypted some of the strings we were intending to decrypt with it at runtime.

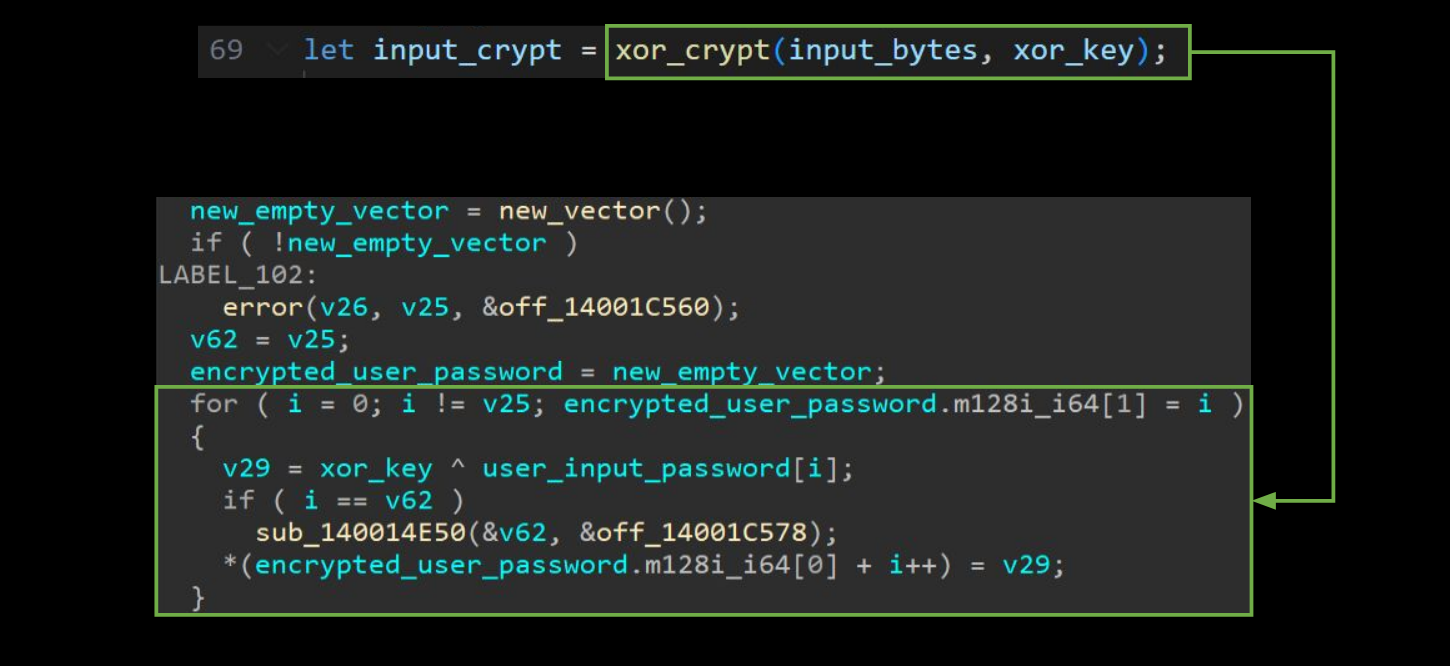

Notably, this did not happen with our password because we were not decrypting it at runtime. Our program still needs the XOR routine to encrypt the user input before comparing it to the hard-coded encrypted password. So what did Rust’s compiler do?

It just inlined the logic for xor_crypt() instead:

Anti-Analysis

Now we know we are at least analyzing the right binary and learned a bit about Rust along the way. If we continue our analysis, we’ll eventually come across the anti-analysis functionality we built in.

Anti-Debug Decompilation

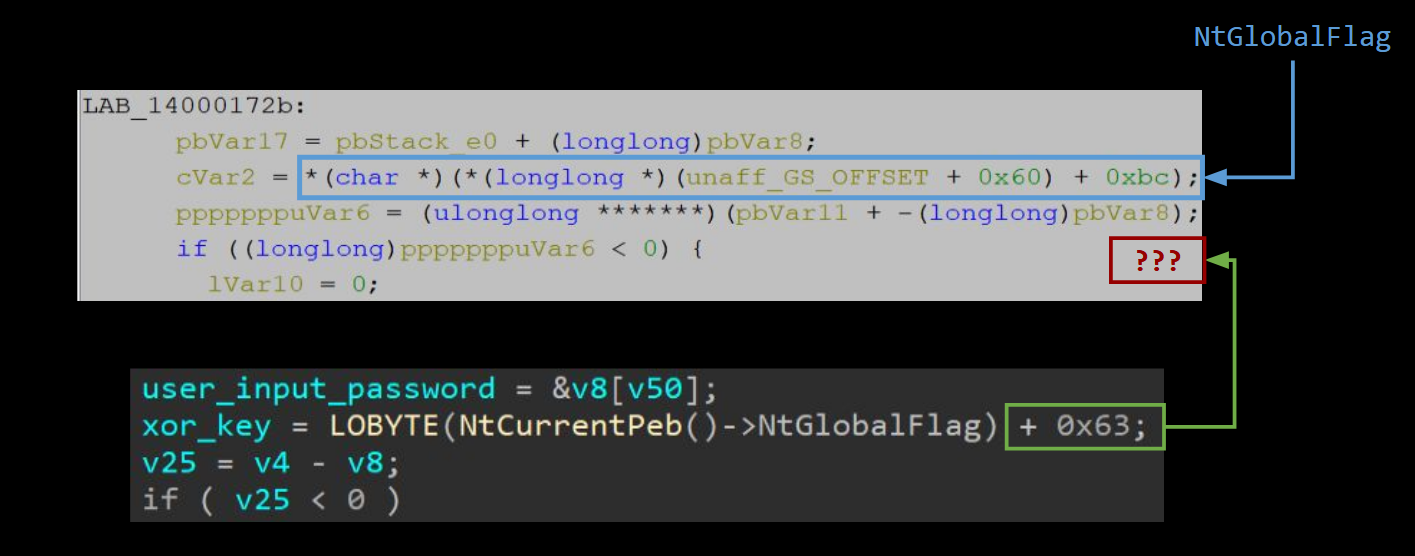

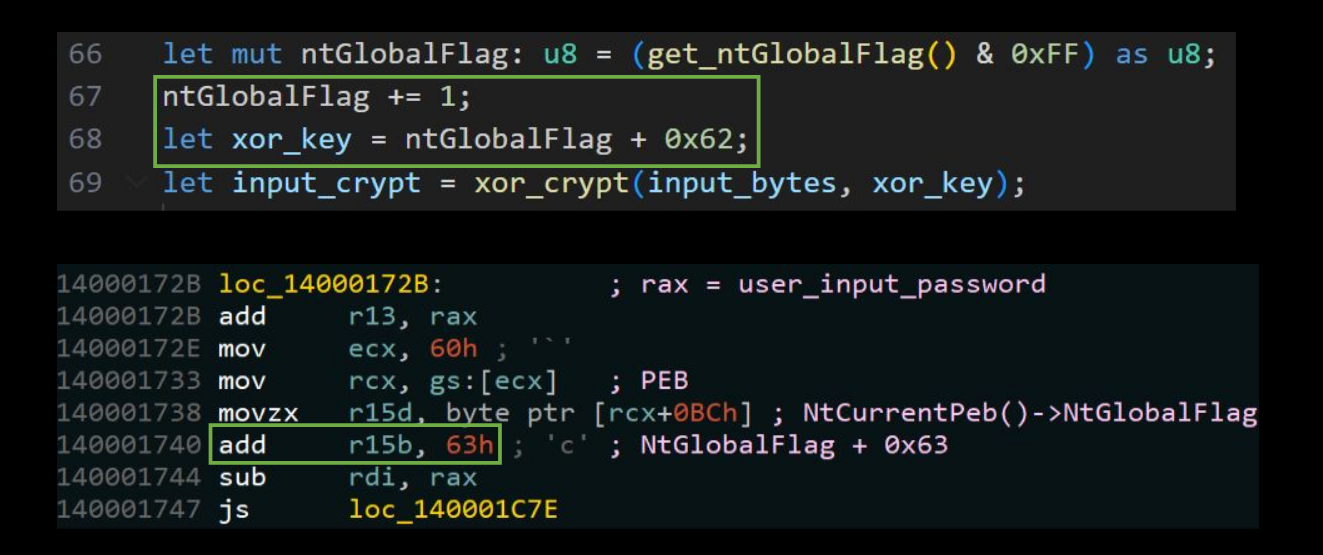

Here’s how the decompilation for the anti-debug feature we added. Like before, Ghidra’s output is not as clean and we have more manual interpretation to do. Such as unaff_GS_OFFSET + 0x60 being equivalent to NtCurrentPeb(). One oddity with the Ghidra decompilation is that it fails to catch the addition of 0x63 to the NtGlobalFlag; it is simply not present:

This decompilation corresponds to the code where we dynamically set the XOR key using the NtGlobalFlag variable. We also see another, but not surprising, optimization: ntGlobalFlag +=1; xor_key = ntGlobalFlag + 0x62; simply becomes xor_key = ntGlobalFlag + 0x63;. Having analyzed this, we’ll know the XOR key for the password is 0x63! This is shown below using the IDA disassembly, but it’s the same on both tools:

At this point we’re pretty close to finding the password! Let’s continue following this code’s execution flow.

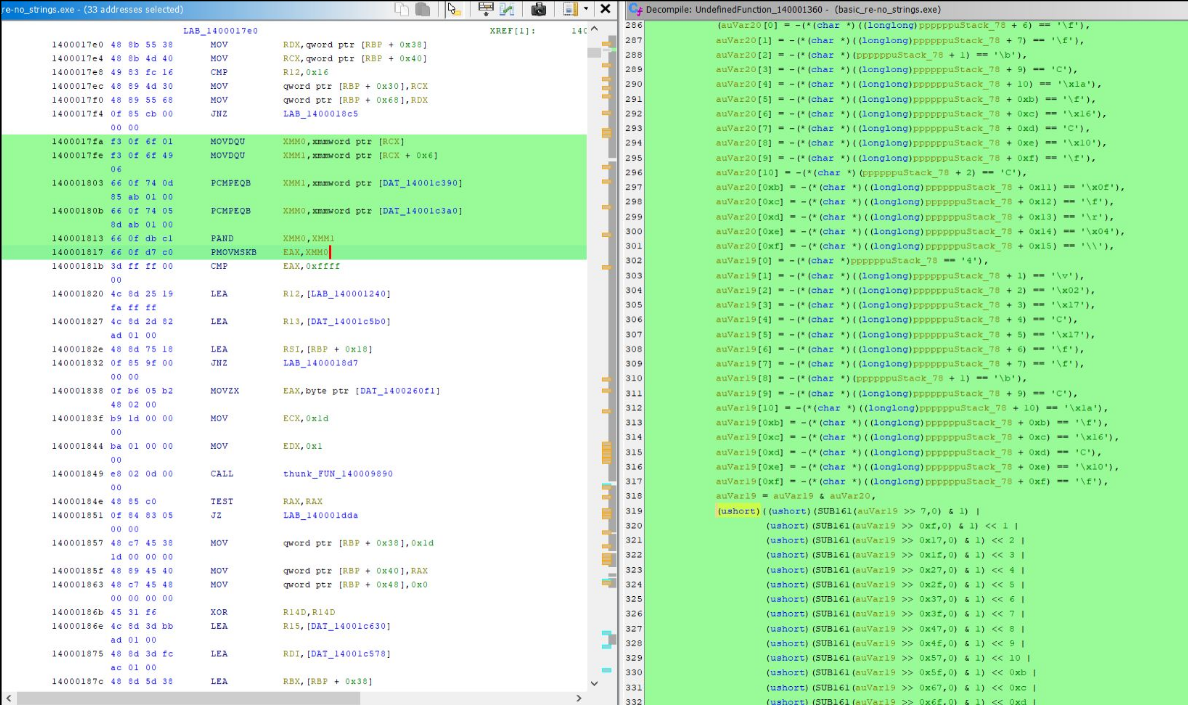

Rust LOVES SSE Instructions

At this point we find the logic for comparing the encrypted password with the XOR’ed user input! Unfortunately, this logic manifests another quirk of Rust… 🙂 its love for SSE instructions! Personally, I think it’s just optimizing for maximum headaches in reverse engineers… but, what do I know?

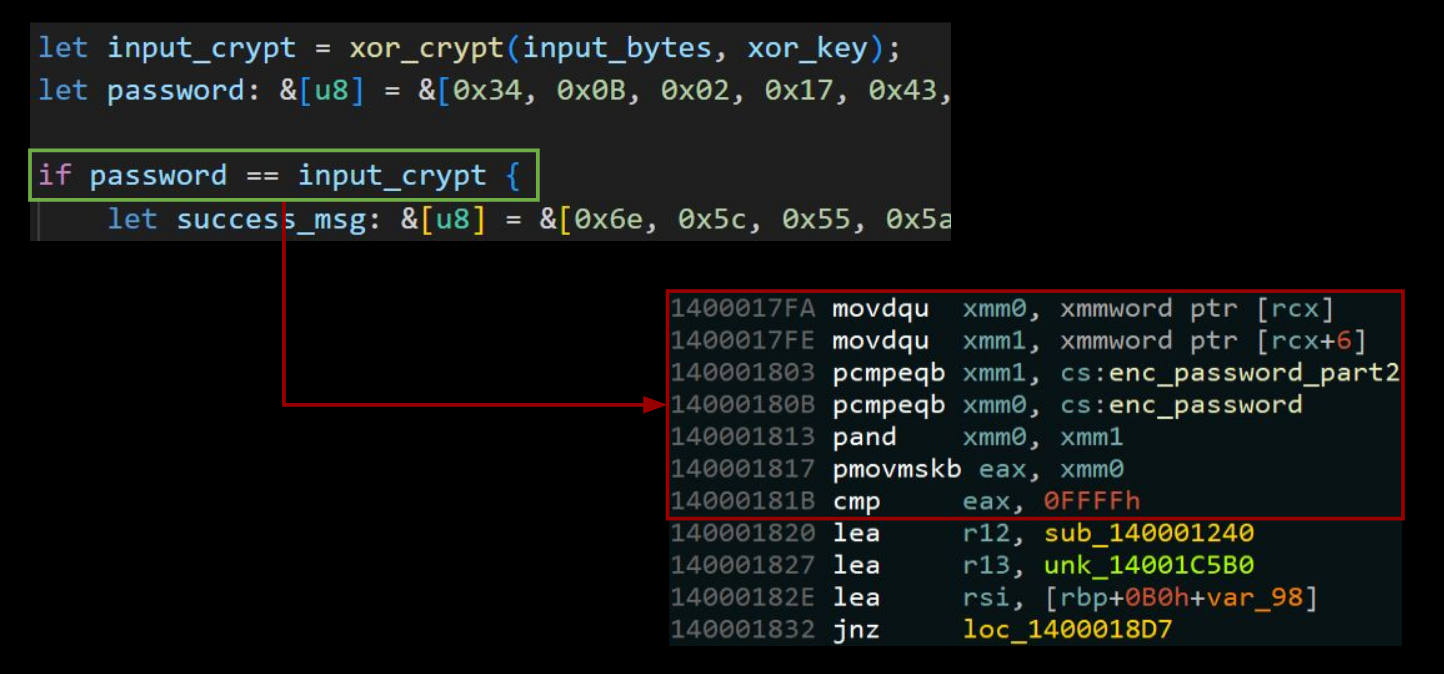

Here’s the disassembly with the corresponding source code we wrote:

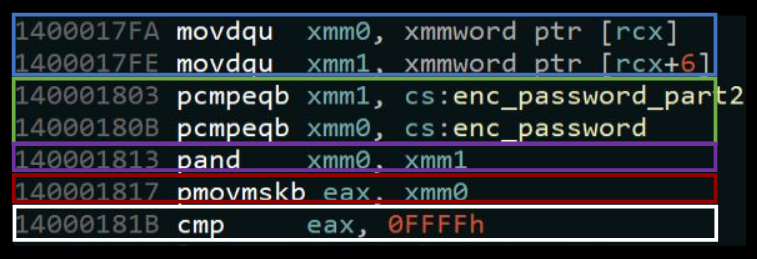

Let’s break down these SSE instructions. Honestly, it’s not that bad, it’s a matter of gaining familiarity with new/uncommon instructions. Below is a color coded breakdown of what the extensions do:

- Load the user password parts in `xmm0` and `xmm1`.

- Compare with the expected values from `.rdata` (encrypted password).

- 128-bit AND the results from each comparison.

- ???

- Compare the result. (Success if `eax != 0x0FFF`).

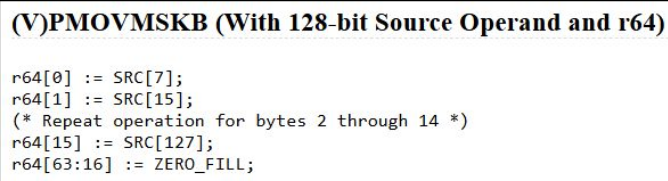

Ok, the pmovmskb needed a bit more room for an explanation. At least it was a bit more difficult for me to wrap my head around initially. Especially when trying to work with a definition like this.

After consulting with my therapist — I mean — ChatGPT, I came to understand that the instruction pmovmskb extracts the most significant bit from every 8 bits of xmm0. Since an xmm register is 128-bits, the result is 16 bits (4-bytes), hence the final comparison to the 4-byte value 0xFFFF.

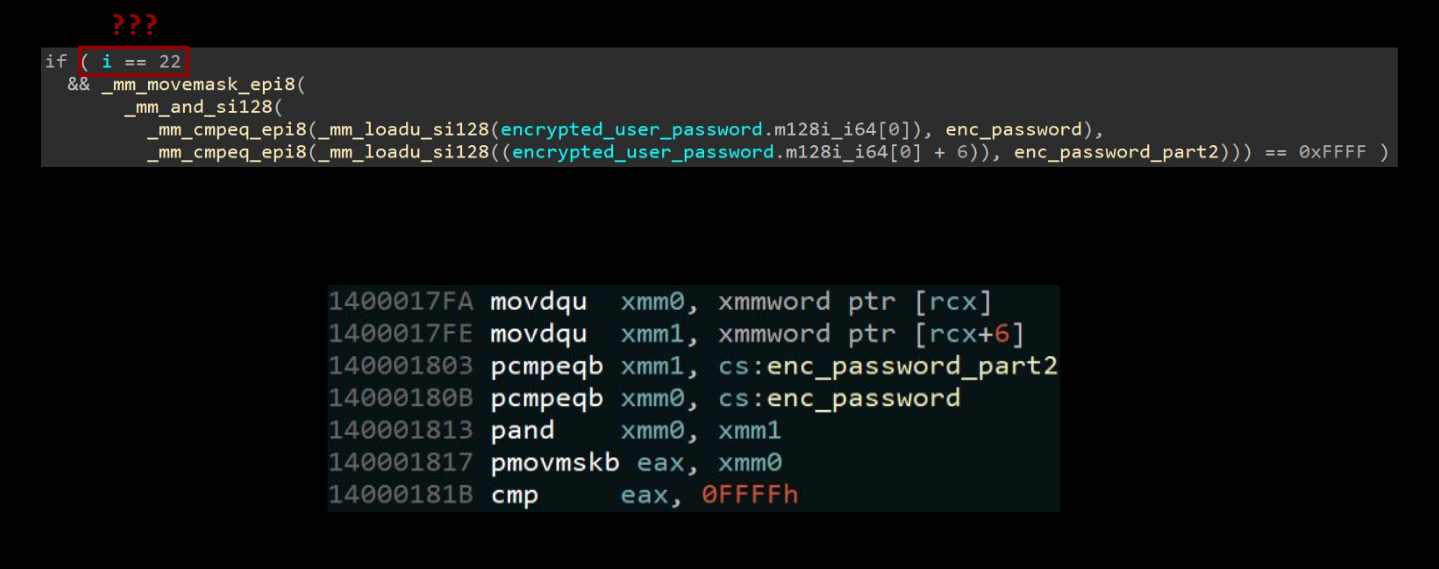

Cool, but how does the decompilation look like?

In this case, both struggled. Below we’ll see IDA’s decompilation which seemingly randomly includes a comparison i == 22? Otherwise, it’s not too difficult to read.

Ghidra on the other hand… had a bit more of a hard time figuring out how to decompile SSE instructions. 🥴😵

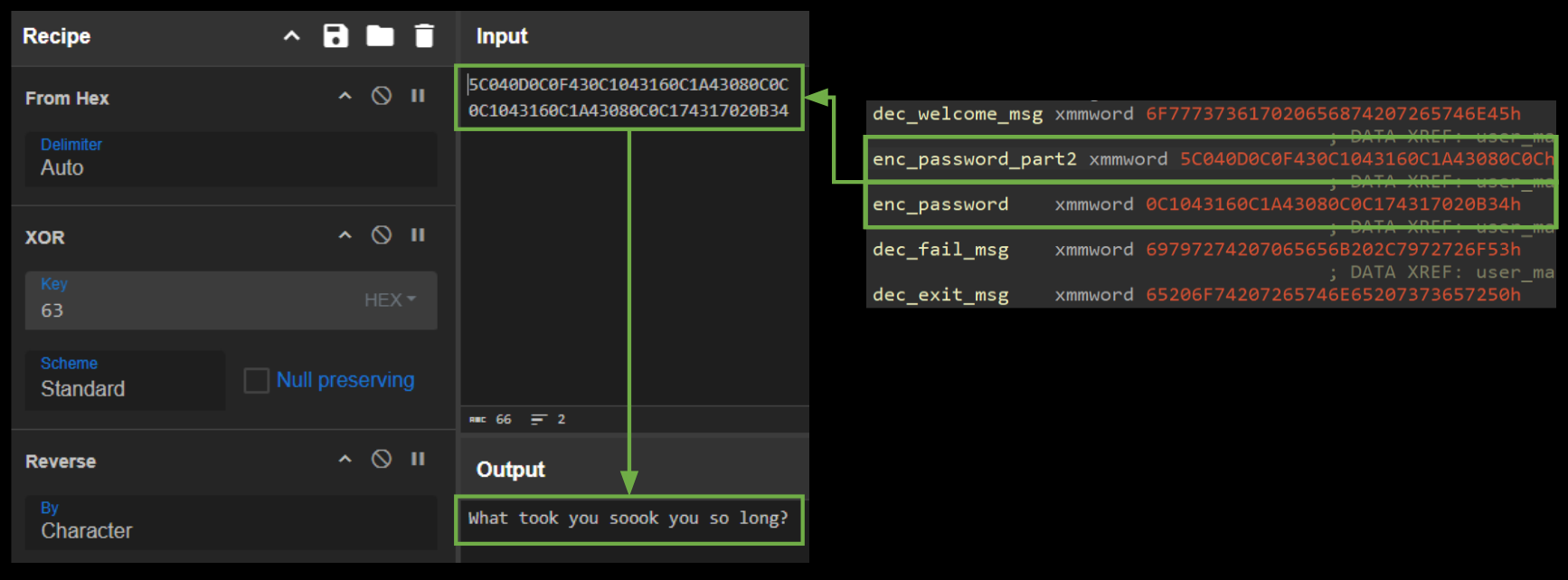

Password Recovery

Now that we understand what the SSE instructions are doing, we know that the hex data from .rdata is the encrypted password… and we have the XOR key from our previous analysis of the anti-debug functionality!

Now we can simply copy the hex data used to compare to the XOR’ed user input into a tool like CyberChef and… we’ve got the password! 🎉

Helpful Resources

- CheckPoint Research Deep-Dive: Rust Binary Analysis, Feature by Feature

- BlackHat Talk on the Rust Malware Ecosystem: Rust Malware Ecosystem